IIDA Tetsunari

Chairperson, Institute for Sustainable Energy Policies

Ten years ago, on March 11, 2011, I was in Potsdam, Germany. I had arrived in Germany the day before on a direct flight from Narita Airport, and the next morning I received news from my wife that Japan had been hit by a massive earthquake and tsunami. Klaus Töpfer, former German Minister of the Environment, hosted a strategy meeting of the International Renewable Energy Agency (IRENA), which had just been inaugurated the year before last, and I was invited with about ten others, including Adnan Amin, Interim Director General of IRENA (who later became the official Director General).

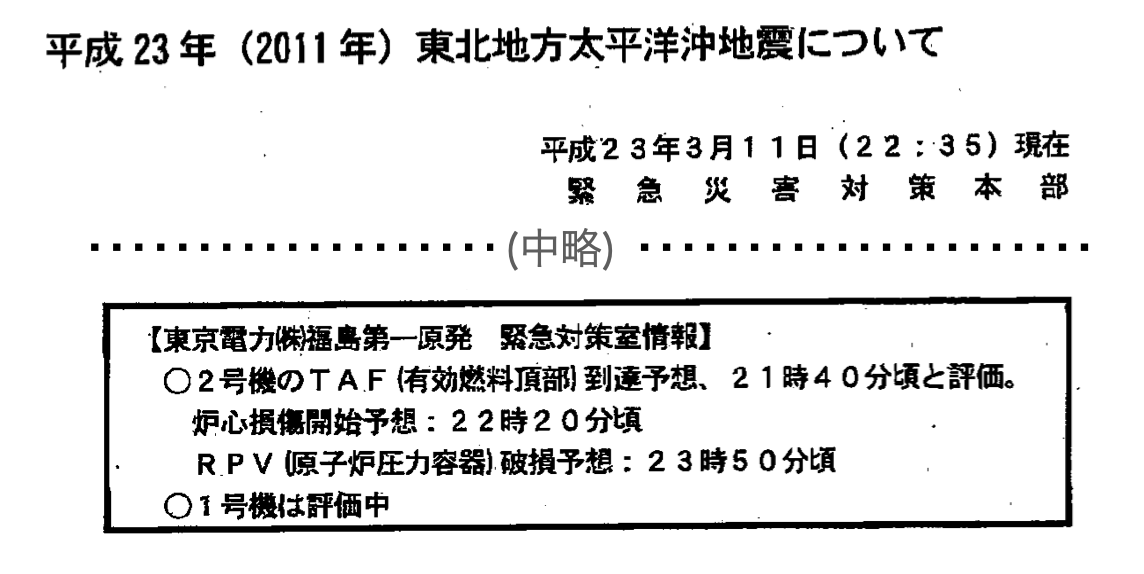

I could not help but be concerned about the consequences of the Great East Japan Earthquake, especially on the nuclear power plants, and while attending the strategy meeting, I searched the Internet for those information. I couldn’t believe my eyes when I saw the following information released on the homepage of the Prime Minister’s Office at 22:35 (Japan time) on the day of the disaster. It said that a meltdown had already started at Unit 2 of the Fukushima Daiichi Nuclear Power Plant (this was later reported to be a misprint for Unit 1, which had a hydrogen explosion the next day). Seeing this, I rushed back to Japan in the midst of the chaos, and right after I arrived at Narita Airport, soon after Unit 3 got hydrogen explosion.

Ten years have passed since the crisis and chaos of the Great East Japan Earthquake and the Fukushima Daiichi Nuclear Power Plant accident. Immediately after 311, I had a hunch that this would be an important turning point in the modern history of Japan. There were certainly some positive changes, but on the other hand, there was also a great deal of backwardness due to the reaction and shakeout, which could be called the “Shock Doctrine,” as a result of the appearance of antiquated and anti-intellectual politics in the immediate aftermath. The accelerating energy transition is making economic and technological progress easier to see, and there are more and more new people who support this trend in Japan, but there is still a long way to go. The degradation of Japan’s political administration with regard to radiation contamination and exposure, which is more complex and difficult to see, shows that the bottom has fallen out of the knowledge society, with Germany and other countries, greatly affected by the Fukushima Daiichi nuclear accident on March 11, taking the lead and then moving left and right as the global renewable energy transition accelerated. Japan may have spent the last decade exposing its dysfunction.

Ten years have passed since the crisis and chaos of the Great East Japan Earthquake and the Fukushima Daiichi Nuclear Power Plant accident. Immediately after 311, I had a hunch that this would be an important turning point in the modern history of Japan. There were certainly some positive changes, but on the other hand, there was also a great deal of backwardness due to the reaction and shakeout, which could be called the “Shock Doctrine,” as a result of the appearance of antiquated and anti-intellectual politics in the immediate aftermath. The accelerating energy transition is making economic and technological progress easier to see, and there are more and more new people who support this trend in Japan, but there is still a long way to go. The degradation of Japan’s political administration with regard to radiation contamination and exposure, which is more complex and difficult to see, shows that the bottom has fallen out of the knowledge society, with Germany and other countries, greatly affected by the Fukushima Daiichi nuclear accident on March 11, taking the lead and then moving left and right as the global renewable energy transition accelerated. Japan may have spent the last decade exposing its dysfunction.

The new coronavirus (COVID-19) has become a global pandemic since the beginning of last year, and in contrast to other countries around the world, the response and response by Japanese politics, government, media, and academia has been remarkably dysfunctional. Although the number of infected people and deaths appear to be lower than in Europe and the United States, this is only due to the good fortune of “Factor X” (Professor Shinya Yamanaka), which is found in East Asia, and Japan has the worst COVID-19 death toll in East Asia. Japan’s response to the outbreak has been far from what one would expect from an advanced country or knowledge-based society. These include the colossal mistake of using a luxury cruise ship that docked in Yokohama as a ” COVID-19 culture ship” for the new COVID-19 infection while the whole world was watching, the ill-conceived and foolish “Abeno mask,” and the overwhelmingly low number of PCR tests, which still ranks around 150 in the world even after one year. Japan’s dysfunctional response to the COVID-19 disaster is the same as the one after the Fukushima Daiichi nuclear power plant accident.

These are deep-rooted problems that are also rooted in Japan’s organizational culture that suppresses and discourages the individual. The mass media has lost sight of its “publicness” and is suffering from complicated fractures. The mass media has subjugated itself, and the academia, which has become politicized and close to the center of power, has actively pandered to the mass media, both of which have abandoned their independence and roles as intellectuals.

In general, it seems to me that the whole of politics, government, academia, media, etc., which make up Japan’s knowledge society, are in a different position from that of the global society. If we are to envision a sustainable Japan for the next 100 years, we need to look at the roots of Japan’s dysfunction that have become apparent over the past 10 years and the past year, and rebuild and update from there. It will not be easy, but in the end, it will come down to the courage of each and every one of us to be independent, to speak out, and to act.